Serious Felonies and Capital Punishment

With over 1,500 executions since 1970, the death penalty has been a part of the United States’ judicial process since its start. However, as previously held ideas about the practice are being questioned, more and more Americans are opposing the use of capital punishment, which may be the major contributor to the decrease in executions or even death penalty sentences in recent years. Used only for the worst of the worst felonies, the death penalty has a number of laws governing its implementation, terms to be aware of, and an interesting history through the progression of our judiciary system. It’s also important to note the methods used, how much it costs taxpayers, state policies, and discussion about its benefits and disadvantages.

Crimes Punishable by Death Penalty

Crimes that can be punishable by the death penalty in circumstances are called capital offenses. After a bit of debate and changes over the year, the term has settled to include include crimes that result in homicide, namely:

- First degree murder

- Murder with special circumstances

- Homicidal Rape

There is still debate about the other crime typically deemed valid for capital punishment: federal treason.

The federal court has some pretty specific guidelines regarding who can be charged with the death penalty, but it will vary pretty widely by state. Some states will qualify all crimes that result in a murder – even if the defendant wasn’t the actual killer, while other states have outlined the worst murders that are specified for their capital convictions.

Methods of Execution

Until the 1880s, most death penalty cases were handled by hanging or a firing squad. The electric chair followed this practice, to be followed by lethal injection after its implementation in 1982, showing there hasn’t been a whole lot of change through its existence.

Lethal injection usually consists of three drugs: some kind of sedative; a drug to paralyze; and a drug that stops the heart. However, a recent Addendum from Attorney General Barr has converted lethal injection to be a single drug called pentobarbital.

While it remains as the primary method for all states with the death penalty and the federal government, some states also allow other options, usually only when lethal injection is deemed unconstitutional or impractical:

Electrocution– Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia

Lethal Gas– Alabama, Arizona, California, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, Wyoming

Hanging– Delaware, New Hampshire, Washington

Firing Squad– Mississippi, Oklahoma, Utah

The Cost

The Judicial Conference Committee on Defender Services reported in 2010 that the federal government’s capital punishment cases cost eight times as much as their non-death ones. There are a few key factors that make the death penalty even more expensive than putting someone in prison for life.

Legal Costs– More often that not, those being tried in a capital case aren’t able to afford their own legal representation, putting that cost, as well as the cost of the prosecution’s legal costs, on the state or federal taxpayers.

Pre-Trial Costs– There’s a lot of preparation that has to go into a case seeking the death penalty. These may require extra time for evidence to be gathered, mental health tests to be conducted, information about past convictions and other history of the defendant, and expert testimony.

Jury Selection– This is more expensive namely because it takes much longer to put together a jury for a capital punishment case. Jurors must be completely unbiased to fulfill the offender’s right to a fair trial.

Trial– Court costs are extended nearly four times as long in these cases, also leading to more costs for detention, lawyers, jurors, and others that require to be paid over the course of the trial.

Incarceration– Because of the extra security and solitary required, imprisonment costs more for those on death row.

Post-Conviction– This mostly involves appeals, as they have the right to bring new evidence to the court whenever something is found. These appeals also cost, as trials have to be held.

Examples of Various States’ Costs:

- Tennessee reported in 2003 that their death penalty trials cost 45% more than those for life in prison.

- Also in 2003, Kansas found that death penalty cases cost them 70% more, with 49% being from pre-trial and trial costs, meaning it does not cost them more to keep someone alive in prison for life.

- Then, in 2008, Maryland found their non-death cases were $1.1 million, while their capital punishment cases cost three times more.

- As of 2011, California had spent $4 billion for 13 executions.

- Oklahoma’s capital punishment cases cost over three times as much as non-capital cases in 2017.

- Creighton University economics professor Dr. Ernest Goss reported in 2016 that Nebraska spends $14.6 million a year upholding capital punishment.

- Along with 4 new death sentence convictions, Texas was responsible for 8 of the 20 executions in 2019. These convictions cost three times as much as life in prison for the state.

What About Cruel and Unusual Punishment?

The Eighth Amendment of the Constitution protects all under its judicial system (citizens or not) from being inflicted with a punishment that fits its qualifications as a cruel or unusual punishment. However, this is more referring to the fact that a punishment must fit the severity of the crime, so the Supreme Court has ruled that, under extreme cases, execution is not a cruel or unusual punishment, but rather a justifiable penalty for the worst crimes. This debate has been sparked more in recent years, as humanity’s standards of cruel and unusual has evolved into something much different than at the conception of capital punishment.

Laws and Court Rulings

There was a point in history when the Supreme Court did find the death penalty to be a cruel and unusual punishment. Citing the discrimination it seemed to inflict on minorities and the poor, Furman v. Georgia deemed capital punishment to be in violation of the Eight Amendment. As the debate revolves around the question of whether execution is a equal response to certain crimes, the answer here was no.

However, this only lasted until 1976 with Gregg v. Georgia, when the law was reinstated in Georgia, Florida, and Texas. These states in particular created laws that provided more specific requirements for a ruling of capital punishment, which the court ruled satisfied the Eight Amendment rights.

From here, the court had a number of trials that helped set the standards for the death penalty today, starting with Coker v. Georgia the next year. This ruled that rape is not an acceptable crime to qualify for execution, further expanding on the idea of the punishment matching the crime.

Even following this trial’s verdict, six of the states held that the death penalty was appropriate for those convicted of rape of a minor, as the prior case left the question of whether this only applied to adult rape convictions. The case of Kennedy v. Louisiana in 2008 closed this question, ruling it unconstitutional.

It used to be allowed for the judge to consider aggravating circumstances that the jury may not have, deeming them “sentencing considerations” in 1990 by Walton v. Arizona, when considering the death penalty. However, Ring v. Arizona (2002) ruled that, according to the Sixth Amendment’s provision of a defendant’s right to a trial by an impartial jury of their peers, it is unconstitutional for a judge to upgrade, so-to-speak, a sentence to that of capital punishment.

Next came verdicts regarding the types of individuals who could be committed to the death penalty, regardless of their crime. This began with Atkins v. Virginia, also in 2002, considering those with severe mental impairments being executed a condition of cruel and unusual punishment. This was expanded upon 12 years later when Hall v. Florida decided that an IQ test is not valid representation of someone with mental impairment eligible for this distinction. Likewise, Roper v. Simmons qualified the same to be true of juvenile offenders in 2002.

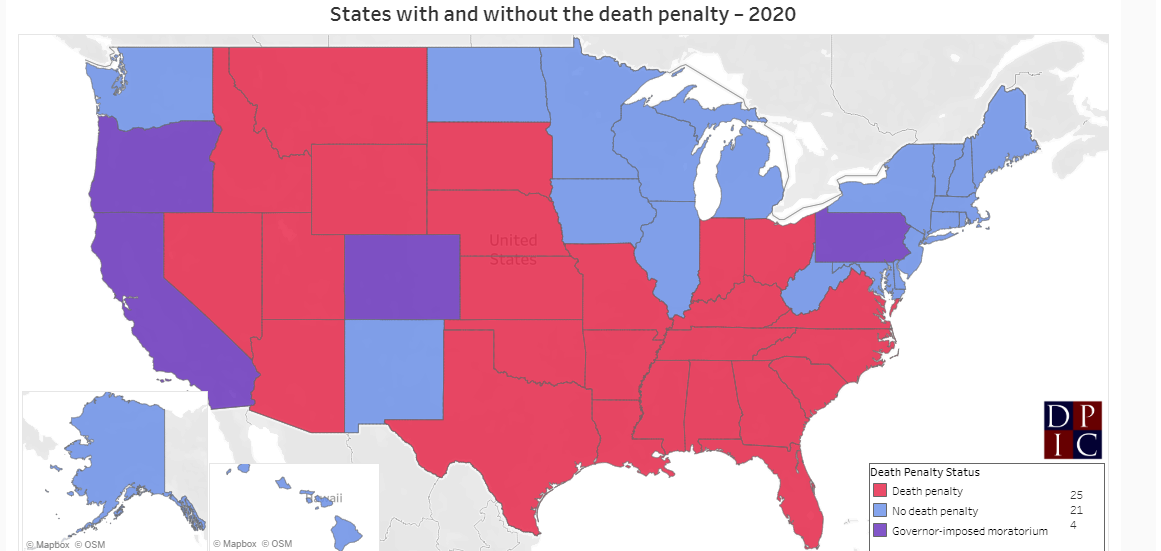

State Policies

The following states still implement the death penalty:

- Alabama

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Florida

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Indiana

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- North Carolina

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Virginia

- Wyoming

The following states abolished the death penalty, in this order:

- Michigan (1847)

- Wisconsin (1853)

- Maine (1887)

- Minnesota (1911)

- Alaska (1957)

- Hawaii (1957)

- Iowa (1965)

- West Virginia (1965)

- Vermont (1972)

- North Dakota (1973)

- Massachusetts (1984)

- Rhode Island (1984)

- New Jersey (2007)

- New York (2007)

- New Mexico (2009)

- Illinois (2011)

- Connecticut (2012)

- Maryland (2013)

- Delaware (2016)

- Washington (2018)

- New Hampshire (2019)

States also differ in their frequency of offering clemency, which is when a governor, president, or administrative board decides to reduce a sentence. For death penalty cases, this involves removing their death sentence. With only a total of 290 clemencies in the whole United States, Illinois leads the pack largely at 187 with a gap with Ohio of 166, while Alabama, Delaware, Idaho, Montana, and Nevada have each only granted one.

Differing Opinions

There are a few reasons why people advocate for the death penalty, the biggest usually that it is believed to be a deterrent for crime. The idea is that, if there’s the threat of a death penalty as a result of a crime, offenders will be more hesitant to commit these crimes. Many also cite justice being served to those who committed the ultimate act – taking someone’s life – meaning they forfeit their rights to their own life. Finally, many believe victims’ families receive closure by seeing the killer behind bars and then facing the worst punishment available.

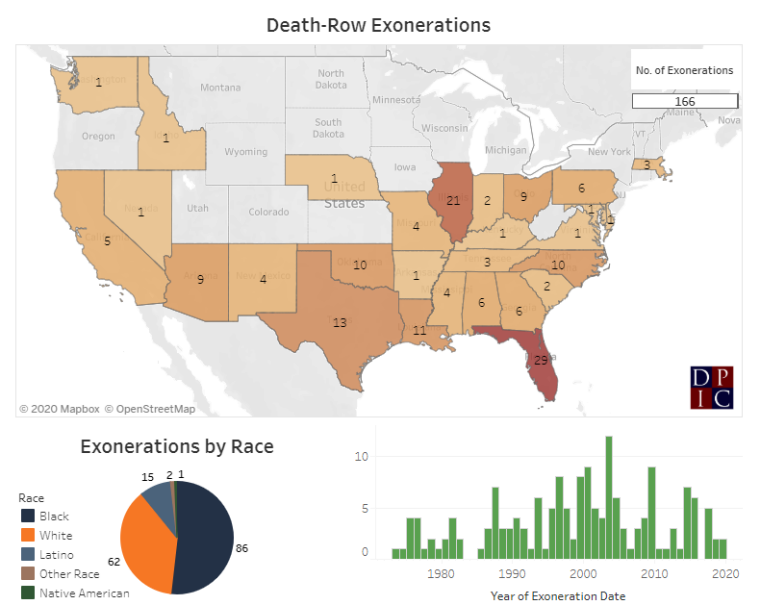

Alternatively, many are passionate about the harm that the death penalty has on society and its victims, explaining several reasons against the policy. Firstly, there is the statistic that over 165 offenders on death row were found to be innocent and exonerated since 1973. This is concerning to many, as it shows that the flaws in our judicial system may be detrimental when assigning capital punishment. They also fight against the claim that it deters crime, explaining that there has been no real evidence of this thus far.

Further examining the impact it has on the system, opposers explain that being sentenced to death shortens an individual’s right to due process, as the case cannot be retried after their death. It also displays inconsistency in its sentencing, which makes it unfair to those who have more lenient judges or juries, as well as weakens the impact it has on deterring crime.

Additionally, they argue that capital punishment does, in fact, indicate cruel and unusual punishment, especially as debate surrounds how much pain is felt during the course of lethal injection and other execution methods. There is an especial contradiction here, for some, as the death penalty is meant to show the severity of taking a human’s life, and yet does so by also taking a human’s life, making some question the statement it says about the value that the country has for its citizens’ lives.

This also follows when statistics by race are analyzed, which show that a murder with a white victim is four times more likely to result in capital punishment. Statistics also find that around 35% of those on death row are black, just since 1976 – following a rate of 53% before this point, which is incongruent with the race’s overall population of the US, which is only 13%. Others can find themselves with a less-than-fair conviction because their social or wealth standing prohibits them from having the best representation possible.

Exonerations

To further examine one of the most widely used arguments against the death penalty – that the innocent are too often convicted of capital punishment, exonerations happen for one out of ten inmates on death row. In fact, for all crime, there are over three exonerations every week, a number that continues to increase as there are more methods of proving innocence growing.

The National Registry of Exonerations found that wrongful death penalty convictions are most often a result of official misconduct and perjury or false accusation. Those who disagree with the penalty use this as evidence of how unreliable evidence can be, meaning that it can be unfair to sentence someone to death over evidence that isn’t completely factual. The Innocence Project found these factors to heavily contribute as well:

Eyewitness misidentification

False confessions or admissions

Government misconduct

Inadequate defense

Informants (e.g., jailhouse snitches)

Unvalidated or improper forensic science

DNA evidence has seen a massive increase in effectiveness, especially as technology improves every year. Not limited to death penalty cases, DNA has exonerated 367 individuals since 1989, 130 of these being murder cases. Sadly, most are under 27 when their wrongful convictions occur but are not exonerated until nearly 43, with 61% being African Americans. Some argue that this further perpetuates the race issue, as well as allows the real perpetrators to walk free to commit other crimes while a non-offender serves time or even loses their life.

Where Are We Now?

Today, death sentences have decreased by over 50% within the last decade (2010-2020), which is 89% from its peak in the 1990s. This number saw n even faster decrease from 2015-2020, with only 39 new death sentences, showing that it’s slowly being done away with as support for the policy dwindles. In this period, actual executions fell by nearly 43% as well, meaning that some of these death penalties aren’t actually being carried out.

However, we also saw the end of a twenty year gap from the fervor that the ’90s saw, with Trump’s Administration resuming their call to death penalties. Attorney General William P. Barr made the orders for a Federal Execution Protocol Addendum, stating that, “The Justice Department upholds the rule of law—and we owe it to the victims and their families to carry forward the sentence imposed by our justice system.” This adopted protocols from some of the states known for their strict laws regarding the death penalty, such as Georgia, Missouri, and Texas. It also scheduled the execution of five offenders in particular.

The death penalty has had great changes over the course of its existence, seeing surges and declines. Despite the current administration’s emphasis on capital convictions, public support for the death penalty is at 40%, a record low for the country. While there has been ample debate about the benefits and morality of capital punishment, it is unclear where the future lies for this conviction. However, its high cost compared to non-death cases may lead to further examination on the topic in the years to come. Additionally, many organizations are coming forward to share the frequency of exonerations and what that means for those on death row and their possible innocence. Laws continue to place more restrictions on when this penalty can be applied, yet we’ve seen in the past that those cases are sometimes altered. While these discussions continue to occur on a national and state level throughout our judicial system, it is sure to see greater change throughout the next decade.